You can’t search for women in the State Papers Online. There’s no way of knowing how many letters they wrote, or received, or how often they were mentioned. If you know the name you’re looking for you can search through the descriptions and abstracts, but you would need to watch out for spelling variants or mistakes. This method also doesn’t help estimate how many letters there are overall, and it limits the possibility of the chance discovery of women’s writing in the archive. As in other datasets, for example wikipedia/wikidata, women’s sources are under-represented. However, things are changing. Projects, notably WEMLO, have spent considerable resources labelling female authors and extracting women’s letters from the union catalogue, Early Modern Letters Online. The RECIRC project has systematically extracted mentions of written works by women found in the letters of the Hartlib Papers, and the upcoming version of the USTC will highlight printed works written by women. Women in the English State Papers have been the subject of significant study over the past few years, most notably Nadine Akkerman’s work on female spies and intelligencers, but as yet letters by women in the electronic database have not been tagged. How might we approach this in State Papers Online?

Women in SPO: A Computational Approach

Manually combing through the metadata for the 160,000 or so letters in SPO looking for female authors would be a worthwhile task but outside the scope of the Networking Archives project. However, we decided to explore a much quicker computational approach, which isn’t a replacement for a properly curated dataset, but it can help to gather some statistics on women’s involvement in the State Papers, and point to some particularly interesting cases.

One way to do this is to write a script to search through the author and recipient fields looking for womens’ names. This is a more difficult task than you might think, for a few reasons. Men and women’s names are often interchangeable, and their usage changes over time. SPO has spelling mistakes and variants, and many author and recipient names are unknown or ambiguous. There are some fully automated methods for detecting gender, such as the Gender package for R, developed by Lincoln Mullen, which uses historical datasets of names and their frequency to predict gender, or this method using a Python package NLTK, which uses machine learning to classify first names, by picking up patterns in the individual characters of a name (those ending in ‘a’ are more likely to be female, for example).

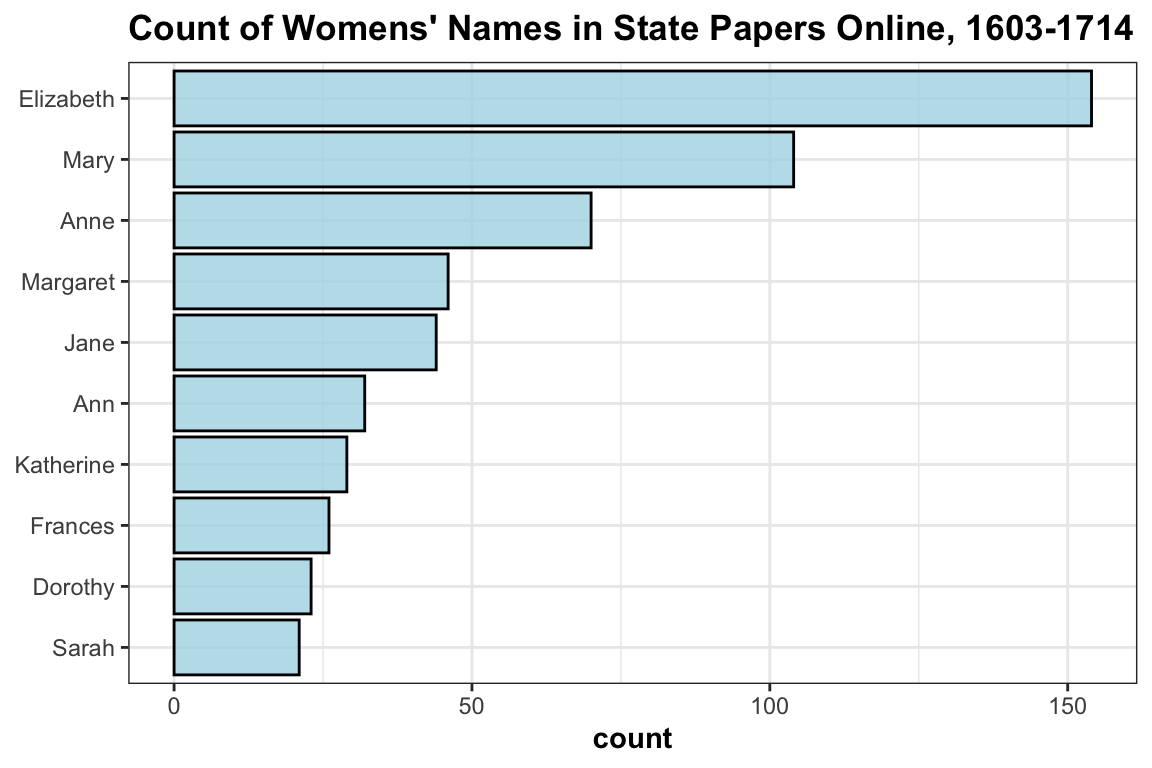

Neither of these are totally satisfactory. Instead, we decided on a mix between automatic and manual methods. The first step was to construct a list of likely female names. For this we started with the full list in the Gender package, and added a bunch of other names or terms that were likely to help find women’s names, including titles such as Lady, Duchess, Queen and so forth, and some other names which we noticed were missing and were common at the time. What this list doesn’t pick up are abbreviations or initials, or spelling mistakes and variants, and we did also add a few of these manually, where we knew the author of a letter was female. This resulted in a master list of names which were then all individually checked. In total we found 1,100 women (either authors or recipients of letters), with just over 230 unique first names. You can see in the chart below that a few names are particularly popular: Elizabeth is by far the most commonly-found, followed by Mary, Anne, Margaret, and Katherine.

Women as Letter-writers

Through these methods we have found approximately 2,400 letters written by about 900 women, though this result should be taken as preliminary and there are almost certainly more to be found (our initial algorithm, which checked through a list of both modern and historical names. missed out Aphra Behn, and there are likely others with non-standard names or initials which have also been overlooked). This represents about 1.5% of all the correspondence in State Papers Online.

In the interactive treemap below, you can explore the distribution of letters written by women in the various series of the State Papers. This shows that the most notable is Elizabeth of Bohemia, the author of 307 letters in SPO and recipient of 151, mostly in SP 16 (SPD, Charles I) and SP 81 (SPF Germany). SP 29 (Charles II) contains several hundred letters written by women, including nine letters written by Elizabeth Maitland, Duchess of Lauderdale, 2nd Countess of Dysart to the 1st Earl of Inchquin under various aliases (others are found in SP 78, along with some of his responses), and ten letters of news written by Ann Bower, who along with her husband Richard kept a coffee shop in Great Yarmouth and together are some of Joseph Williamson’s most prolific correspondents.1

Queen Mary II of England, Queen Marie, Henrietta of Lorraine, and Queen Anne of England are also authors of significant numbers of letters in SPO, as well as the famous female spy, Behn: SPO contains 12 letters sent by her from Antwerp. These letters document her intelligence work and use of ciphers2, make mention of her dealings with other spies such as ‘Celadon’ (William Scott), and Joseph Bampfield3, as well as her struggles with money.4 SP 21 (the Derby House Committee Papers) is notable for containing not a single letter by a female writer, as is SP 79 (SPF Genoa) and SP 93 (Sicily and Naples). These are the exceptions to the rule, however. Some of the female voices found are from small family collections or bundles of intercepted letters, such as those written by Sarah Bardsey to her nephew Peter Fabian regarding a legal case involving some property, which seem to have made their way to the State Papers via the Court of Wards5, an episode which culminated in her being sued for not vacating a house following its sale.6

Intelligencers

The role of women in the State intelligence network requires some further digging. We know from the work of Nadine Akkerman that women played an important role in seventeenth-century spying and intelligence-gathering, but it is clear they were closely involved in the more everyday, ‘newsy’ type circulation of information, too. The suggestion by some historians that women were less interested in news is borderline absurd. There is ample evidence that women were key players in Joseph Williamson’s network of informants. One Ann Bower ran a coffee house in Yarmouth along with her husband and from here the couple distributed and collected news. Lady Utricia Swann wrote to Joseph Williamson (who was then in Cologne) from Hamburg, relaying and commenting on international news, though she added in one letter, ‘I dare not venture to wryte any niews least your Excellency should thincke mee a busie woman’,7 something of a joke considering all her letters to him either contained news or complained that she had none.8 There was at least one female postmaster, in Plymouth, and women, known as ‘book women’ or hawkers, were employed by the head postmaster, James Hickes, to distribute the official Government newspaper, the London Gazette. Evidently their services were highly sought-after by the post office, to the extent that Hickes was worried that they might be poached by another news writer, Henry Muddiman, if not compensated properly— and on occasion, at least, they also acted as informants to Williamson and Hickes in their own right. Women were represented in the upper ranks of the intelligence administration, too: Katherine Stanhope held the office of postmaster general from 1664.

Petitioners

Even more so than with men, the data has a skewed distribution: a few authors write large numbers of letters, and a large number of authors write very few each. In fact, out of 934 found female writers, 637 (68%) author just a single letter (the equivalent number for men is 12,734 out of 20,915 writers, or 60%). The most frequent recipients of these one-off letters are Charles II (86 letters), William Cecil (70), Joseph Williamson (48) and the Admiralty (35). Many of these women were petitioners who wrote letters to the authorities asking for pardons or favours. Examples we’ve found include Margaret Gamlyn, who in 1686 petitioned James II for the release of her son-in-law, imprisoned for his part in the Monmouth Rebellion9, Dorothy Mervyn who wrote to William Cecil asking for a lease on her son’s inherited manor to be settled10, or Sara De Callaway, who asked to be kept on as the supplier of ‘white starch’ to Queen Anne of Denmark as she had to Elizabeth.11 One-off letters to the Admiralty, in particular, are usually petitions asking either for relief following the death of a husband12, or pleading for arrangement of a prisoner exchange, such as Mary Hatfield’s letter written in 1657, whose husband had been captured and was held by the French at Dunkirk.13 These letters were obviously the culmination of significant effort to navigate the necessary naval and legal bureaucracies to secure release: generally they include the name of a specific enemy prisoner to be exchanged, plus a certificate from the relevant authorities stating that the prisoner was in their custody.14 One exception to these petitioners is Alice Hutton: in 1657 she wrote to re-negotiate her contract with the Admiralty to supply them with leaden shot.15

Women as Letter Recipients

SPO contains fewer letters received by women, which is unsurprisingly as the recipients in a Government archive tend to be politicians, monarchs or administrators, and few of those positions were available to women. In total we’ve found 936 letters, received by 261 women. Though again at the top of the list are many monarchs and noblewomen (Elizabeth of Bohemia, Queen Anne, and Queen Henrietta Maria are among the top ten), some lesser-known women are also present in large numbers. The woman with the third-highest number of letters received now in State Papers Online (57) is one Hannah Ferguson. Ferguson received letters from her husband Robert who was implicated in the Rye House Plot and fled to Amsterdam: his fifty letters sent to her, most likely confiscated, make it clear she was acting as a conduit and source of intelligence from their home in Hatton Garden while he was in exile. Her own voice is mostly absent, save three letters, one written to Robert detailing a search of their home16, and an unfinished draft of a letter written on the back of one of her husband’s, which is duly noted by the calendar.17

Women Writing to Women

Rarer still are letters sent by a woman to another woman - we’ve only found 64 out of all 160,000 in the State Papers with these methods. Many of these are between monarchs, such as those to Queen Anne of England/Denmark sent from Queen Marianne of Portugal18, Elizabeth of Bohemia19, and Queen Marie of France.20 In the even rarer instances of letters between women not heads of state, we find a tantalizing glimpse of alternative channels of communication. In 1618 the English courtier Elizabeth Raleigh wrote to Lady Joyce Carew to ask her to use her influence with Thomas Wilson, the second keeper of the Paper Office to convince him to stop the pursuit of her husband Walter’s personal library and archive, as it was, she said, all he had left her son.21 His mechanical instruments had already been confiscated, she added, and though she was promised them back, it hadn’t happened. One of them was worth 100 pounds (£13,000 in today’s money, according to the National Archive’s currency converter). Others who used a similar alternative channel include Dorothea Helena Stanley, Countess of Derby, who wrote to Lady Killegrew, sister of Margaret Cavendish asking for her to petition on behalf of a Mr. Calcott who had killed a man in self-defence.22

Charting Women’s Letters Chronologically

As well as highlighting interesting letters or collections, the matching allows us to chart more accurately the extent of womens’ letters in the State Papers as they occur in time. The chart below is the count of letters identified as written by women across the Stuart period and found in State Papers Online.

While it looks very uneven, it broadly reflects the chronological shape of the State Papers data as a whole: there’s very little correspondence by any gender for most of the civil war years, a time when letters by women are almost non-existent. A couple of periods stand out: there’s 223 letters sent between 1636–1639, mostly by Elizabeth Stuart to Thomas Roe, Henrietta of Lorraine to Balthazar Gerbier, and Queen Christina of Sweden to Charles I. But by far the most notable single year is 1683, which has 86 letters written by women, standing out in great contrast to the years before and after. These are mostly petitions written to Charles II, written in the aftermath of the Rye House Plot, by wives and mothers, either asking for their loved ones to be released, asking for them to be given better lodgings, or to be allowed a visit.

Mapping Women’s Letters

The letters are linked to geographic data and with this it is possible to map the origins of the letters by women. Unfortunately the majority of women’s letters do not have this geographic information, so there’s little point looking for representative patterns. Those letters that do have this information are concentrated in England, particularly London, as well as a cluster sent from The Hague. Those from the latter are mostly Elizabeth of Bohemia writing to the diplomat Thomas Roe, plus some letters of introduction from Amalia of Solms-Braunfels, Princess Dowager of Orange and grandson of William III.

Other prominent places include Lisbon, where the Queen-Regent of Portugal Luisa de Guzmán wrote numerous times to her son-in-law, Charles II; Hamburg, mostly letters sent from Lady Utricia Swann to Joseph Williamson, and Great Yarmouth, thanks to the abovementioned Ann Bower. Dublin also features, and here the four letters written by Susanna Durham stick out: in 1675 she wrote repeatedly to Secretary of State Joseph Williamson trying to secure employment for her husband, who had been stationed in Inis Boffin an island off the west coast of Ireland which she described as ‘the furthermost place of this kingdom’.23 The farthest-off letter, from London’s perspective, is that sent by Jane Wyche, wife of Peter, Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1627–1641, to Francis Windebank, congratulating him on his appointment as Secretary.24

Women mentioned in letters:

Finding mentions of women in the SPO descriptions, or abstracts, is another worthwhile task. Others have done this work manually, but it’s not currently feasible to go through all 160,000 letters in the State Papers by hand and note all mentions of women. The approach we took was to use a Python library called SpaCy, which annotates text using Named Entity Recognition (NER): an automatic method for detecting parts of text such as people, organisations, or places. First we ran the abstracts through the SpaCy algorithm, and then filtered the results for first names found in the list of womens’ names described above.

This data is very messy, because SpaCy picks up lots of non-names, and these have to be filtered out. Out of about 340,000 name mentions, about 6,000 are identified as belonging to women, plus another 3,000 instances of the word ‘Queen’ without any more identifying information. Not all of these are references to actual women. The first on the list after ‘Queen’ is Mary Rose, which is the name of a ship from where letters were sent in the 1640s.

token | n |

queen | 2,826 |

mary rose | 238 |

queen elizabeth | 208 |

queen anne | 104 |

sarah bardsey | 85 |

henrietta maria | 72 |

queen anne 's | 69 |

saint mary 's | 58 |

queen elizabeth 's | 56 |

saint helen 's | 48 |

The first highest-ranking ‘genuine’ reference to a woman is Queen Elizabeth, perhaps surprisingly for a dataset which starts on the date of her death. These mentions are generally found in letters involving legal matters, usually explaining some background information to a suit by starting with ‘in the reign of Queen Elizabeth…’. Many of the others in the top 100 list above demonstrate the difficulty of getting good results this way: Sarah Bardsey is actually a sender and recipient of letters rather than a mentioned person, something which has not been caught by the automatic methods. The mentions of Henrietta Maria are split between the ship and the person; the references to Saint Mary’s are to various churches, and Saint Helen’s is a town in Merseyside.

Slightly further down the list we come to more genuine references to women. Lady Elizabeth mostly refer to Elizabeth Stuart, the oldest daughter of James VI/I, who was the subject of much communication at court. She is mentioned in letters from Sir John Harington, who for example asked Robert Cecil if she could be brought to Whitehall from his house in Kew, as his son was showing signs of measles25, letters of news relating to her suitors26, and finally news of how her journey with the Count of Palatine back to Germany, and their reception across Europe.

There’s a group of correspondents interested in Lady Elizabeth Hatton, who has 42 mentions. She featured regularly in letters of news from the court. Lady Pembroke is Lady Anne Clifford, who was the hereditary High Sheriff of Westmoreland, and in control of the pocket borough of Appleby. Most of the letters mentioning her were written by correspondents to Joseph Williamson, who put himself forward as a candidate to be Appleby’s MP in 1668, such as this one to him from Daniel Fleming:

I wrote to Lady Pembroke and got the rest of the justices’ hands to the letter, and send copies of it, and of her reply, that you may know how things stand. Unless you can secure Lady Pembroke, which I fear will be hard to do, you will have a cold appearance of the electors of Appleby, since they dare not go any way but that chalked out by my lady, who is as absolute in that borough as any are in any other. If you could get recommended to her by Lady Thanet, in the place of one of her sons, or could get the Countess to stand neuter, I am confident you would carry it; but I fear she will either nominate one of her grand-children or Anthony Lowther, for whom Sir John appears. Sir George [Fletcher] and Dr. Smith have been very active in your behalf.27

It wasn’t successful: her endorsement and therefore the election went to her grandson, Thomas Tufton, but this episode is an excellent example of how a woman’s influence in the State Papers would be hidden, unless we look farther than the authors and recipients of letters.

Conclusions

Women are underrepresented in the State Papers, even when compared to other sources of early modern correspondence, making it all the more worthwhile to tag or otherwise distinguish their letters so they can be more easily found. By highlighting their letters separately, we learn more about their role in the early modern state, and return to them some of the agency suppressed by the structure of a state archive. Women were important in these networks. What becomes clear using these methods is that women from all backgrounds, from the daughter of a king to the owner of a coffee shop, were heavily involved in state intelligence networks, whether secret or those sharing public news. Women could serve as important back-channels of communication when an ‘official’ line of communication was blocked, their influence was called on to request favours on a third party’s behalf, and they were instrumental in petitioning the state on behalf of themselves, their husbands, sons, or brothers.

Highlighting mentions of women in letters of others presents a more difficult, but arguably more rewarding task, because it is one way to solve the problem that women are far less likely to have their voices present in the ‘standard’ sender/recipient metadata of the State Papers: extracting mentions is a way of highlighting the influence of women in a world where nearly all official government business was articulated—though not necessarily carried out—by men, rendering women artificially silent.

As far as the methods are concerned, a mix of automatic and manual checking seems to work well to capture most letters written by or to women. The recognition of mentioned women’s names in the less structured text of the abstracts and descriptions feels like a harder problem to solve. We hope to try training a classifier to recognise men and women’s names, customised to early modern text, using the Stanford NER, which would still likely be imperfect but may find some more interesting links.

For example Ann Bower to Sir Joseph Williamson, 16 July 1669, SP 29/263 f.11, in which she corrects an item she read in Williamson’s newsletter, regarding an infant who had supposedly died of the plague.↩︎

Aphara Behn to James Halsall, 27 August 1666, SP 29/169 f.47.↩︎

Aphara Behn to James Halsall, 16 August 1666, SP 29/167 f.209.↩︎

Aphara Behn to Thomas Killigrew, 31 August 1666, SP 29/169 f.157.↩︎

Sarah Bardsey to Peter Fabian, 26 April 1653, SP 46/100 f.7.↩︎

Sarah Bardsey to Peter Fabian, 28 December 1657, SP 46/100 f.43.↩︎

Lady Utricia Swann to Sir Joseph Williamson, 06 September 1673, SP 82/12 f.54.↩︎

Eg Lady Utricia Swann to Sir Joseph Williamson, 01 January 1673, SP 82/12 f.88.↩︎

Martha Gamlyn to James II, 30 April 1686, SP 31/3 f.301.↩︎

Dorothy Mervyn to Sir William Cecil, after 1605, Cecil Papers↩︎

Sara De Callaway to Sir William Cecil, 24 May 1612, Cecil Papers↩︎

Margaret Risby to Admiralty, 12 December 1657, SP 18/175 f.85.↩︎

Mary Hatfield to Admiralty, 17 December 1657, SP 18/175 f.117.↩︎

Katherine Mechin to Admiralty, 03 February 1657, SP 18/162 f.12.↩︎

Alice Hutton, widow to Admiralty, 01 January 1657, SP 18/176 f.59.↩︎

Hannah Ferguson to Robert Ferguson, 01 January 1683, SP 29/424 f.229.↩︎

Robert Ferguson to Hannah Ferguson, 17 October 1679, SP 29/442 f.214.↩︎

Queen Marianna of Portugal to Queen Anne, 23 September 1710, SP 89/20 f.167.↩︎

Queen of Denmark to Elizabeth of Bohemia, 26 March 1632, SP 75/12 f.357.↩︎

Queen Marie to Queen Anne of Denmark, 16 August 1603, SP 78/49 f.238.↩︎

Elizabeth, Lady Raleigh to Lady Joyce Carew, 08 November 1618, SP 14/103 f.126.↩︎

Dorothea Helena Stanley, Countess of Derby to Lady Killigrew, 07 May 1665, SP 29/120 f.135.↩︎

Susanna Durham to Sir Joseph Williamson, 17 April 1676, SP 63/337 f.100.↩︎

Jane, Lady Wyche to Sir Francis Windebank, 06 April 1633, SP 16/236 f.32.↩︎

SP 14/62 f.24↩︎

SP 14/65 f.53↩︎

SP 29/233 f.137↩︎