Calendars of State Papers and Networking Archives

Most of the quantitative research on the Networking Archives project has been using the metadata from the digitised correspondence of State Papers Online. Metadata in this sense means everything except the content of the letters: including author names, recipient names, date, place of sending and so on, in the research of seventeenth-century intelligencing. Gale State Papers Online brings together a number of historical primary sources, not only the manuscript images from the State Papers, but also full text versions of the ‘Calendars of State Papers’, a set of printed finding aids mostly produced in the nineteenth century. These printed summaries represent another huge store of data available to us which we also use in the analysis of the data.

The data the project is working with has a complicated history. A typical piece of correspondence now in the State Papers Online data started its life as part of the working papers of a Secretary of State. Secretaries were supposed to transfer all the documents relating to the state to what was then called the State Paper Office. This office was established in 1610 and intended as a central place for the Monarch’s private papers, kept and managed by the secretaries.

In practice it was rarely this simple. Secretaries’ papers were fraught with complex issues of contested ownership. Today many governments assume that any correspondence by a sitting Head of State or a politician in the course of their working day is public property (with lots of limits for national security, of course). Historically the rules have been much more ambiguous. Is a letter from a diplomat containing personal news, sent to a Secretary of State, personal or private?

Even when it was clear that a document was in some way ‘public’, politicians and their heirs often resisted the transfer of their libraries to the state, for a variety of reasons. Private documents could expose secrets they would rather stayed buried but also, and more usually, these libraries were valuable assets to be inherited. Elizabeth Raleigh, wife of Walter, lobbied to stop the transfer his personal library (and scientific equipment) to the paper office after his execution in 1618. It was, she argued, her son’s only inheritance and an important asset for his education. Sometimes these transfers came long after the death of the secretary in question. In the eighteenth century the Conway Papers were ‘found’, by the future Prime Minister Horace Walpole, and split between the British Library and the newly-established State Paper Office. The Cecil Papers, about 30,000 documents, mostly the working papers of Lord Burghley and his son, Robert Cecil, both secretaries under sucessive monarchs, were archived at Hatfield House, where they still remain today, though they have actually made their way to State Papers Online, as we’ll see below.

What the Paper Office did manage to get hold of was sorted into various categories and re-arranged over time, had to survive fires, mould, rats, cooking accidents, and so forth, and generally sat unloved and mostly unseen on dusty shelves, though historians (such as John Evelyn), did request and get permission to borrow bundles of documents and take them home. It wasn’t until the 19th century when efforts were made to make the records more accessible. First, the Public Records Office was established (in 1854 but based on an earlier archival amalgamation in 1838), which moved the records from the Paper Office to a purpose-built archive in Chancery Lane, and made them more accessible to the public.

Format of the Calendars

Sort of parallel to this, efforts were made to produce printed summaries of the documents in the archive, in order to make them easier for historians to use. These were large printed volumes, containing descriptions of all of the documents found in the State Papers, organized mostly by reign. They were produced throughout the century, many edited by women, such as Mary Ann Everett Green, and her niece Sophia Crawford Lomas. History owes these women a huge debt of favour.

Figure 1: Title page of one volume of the Calendar of State Papers Domestic for the reigns of Elizabeth and James I

Digitised copies of these calendars are mostly out of copyright and can be found on Google Books and archive.org. Below is a fairly typical entry. It has the date of the document in the left-hand margin, then an identifier to help find the original document, then usually information on the sender and recipient (and sometimes the place of origin). This is followed by a brief description or summary of the contents, and in this case, followed by noting the number of pages of the original manuscript, and the language if not English.

Figure 2: Typical entry in the Calendar of State Papers, a set of printed finding aids mostly produced in the nineteenth century

Alongside the digitised images of the manuscripts themselves, State Papers Online digitised and processed these calendars. They used OCR (Optical Character Recognition) and manually extracted sender/recipient names, dates, and origins, where available, and linked the calendars to the digitised manuscripts. This means you can do text searches in the calendars and link this to the original manuscript image. The metadata Networking Archives is working with is ultimately based on these digitised descriptions.

Understanding the Calendars with Data Analysis

As anyone who has worked with the calendars will tell you, they have been produced to very different standards and as such they interpret the documents they represent in very different ways. They tend to suffer from an identity crisis: never quite sure if they should be purely a manuscript finding aid or a more useful description. In addition, as there’s no inherent logic behind the inconsistencies other than changing editorial policies, it’s hard to get a sense of in what way exactly they are inconsistent. Data analysis can help with this, by analysing the entire dataset at scale, to understand the changing shape of the printed calendars by time, topic, and office.

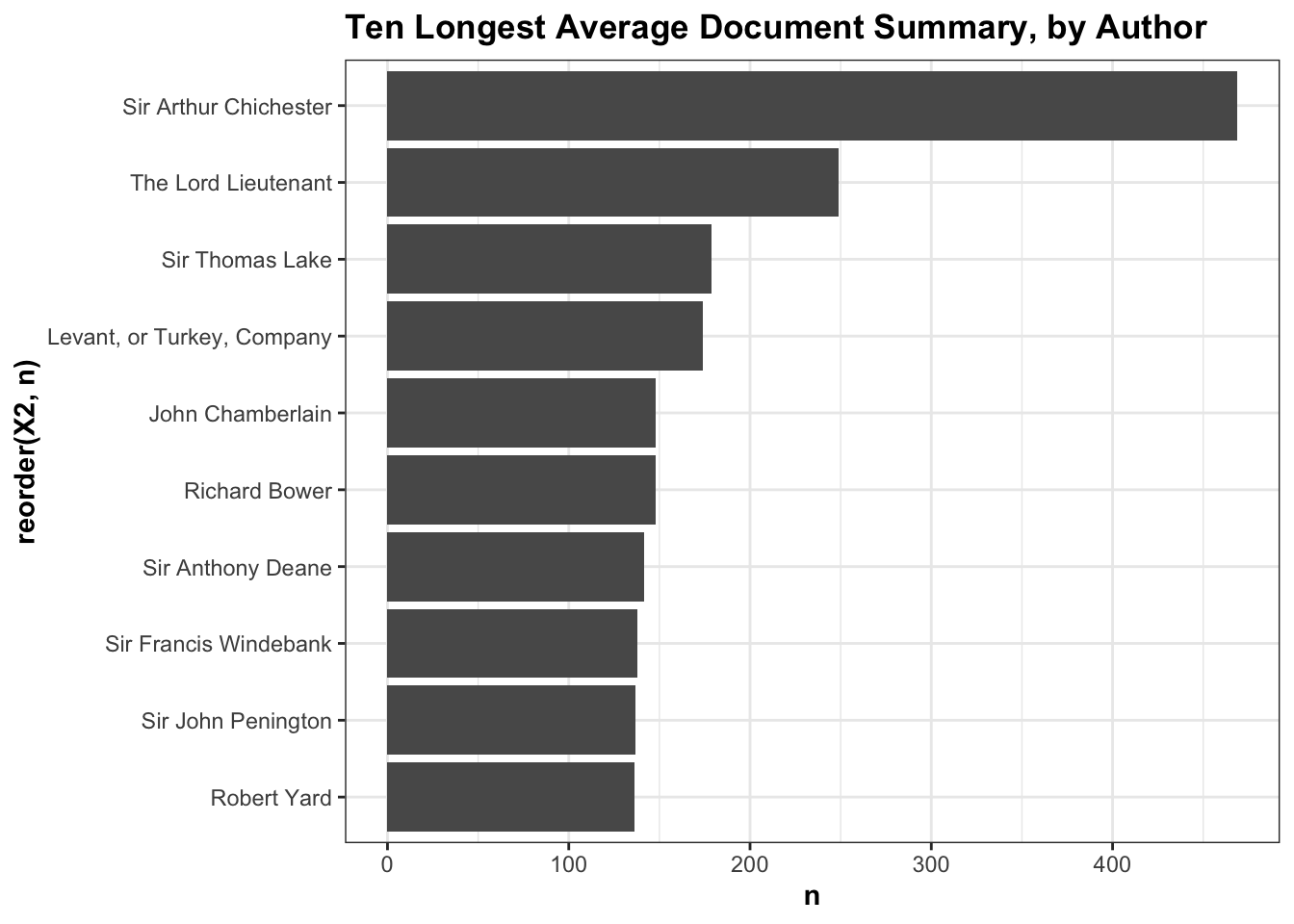

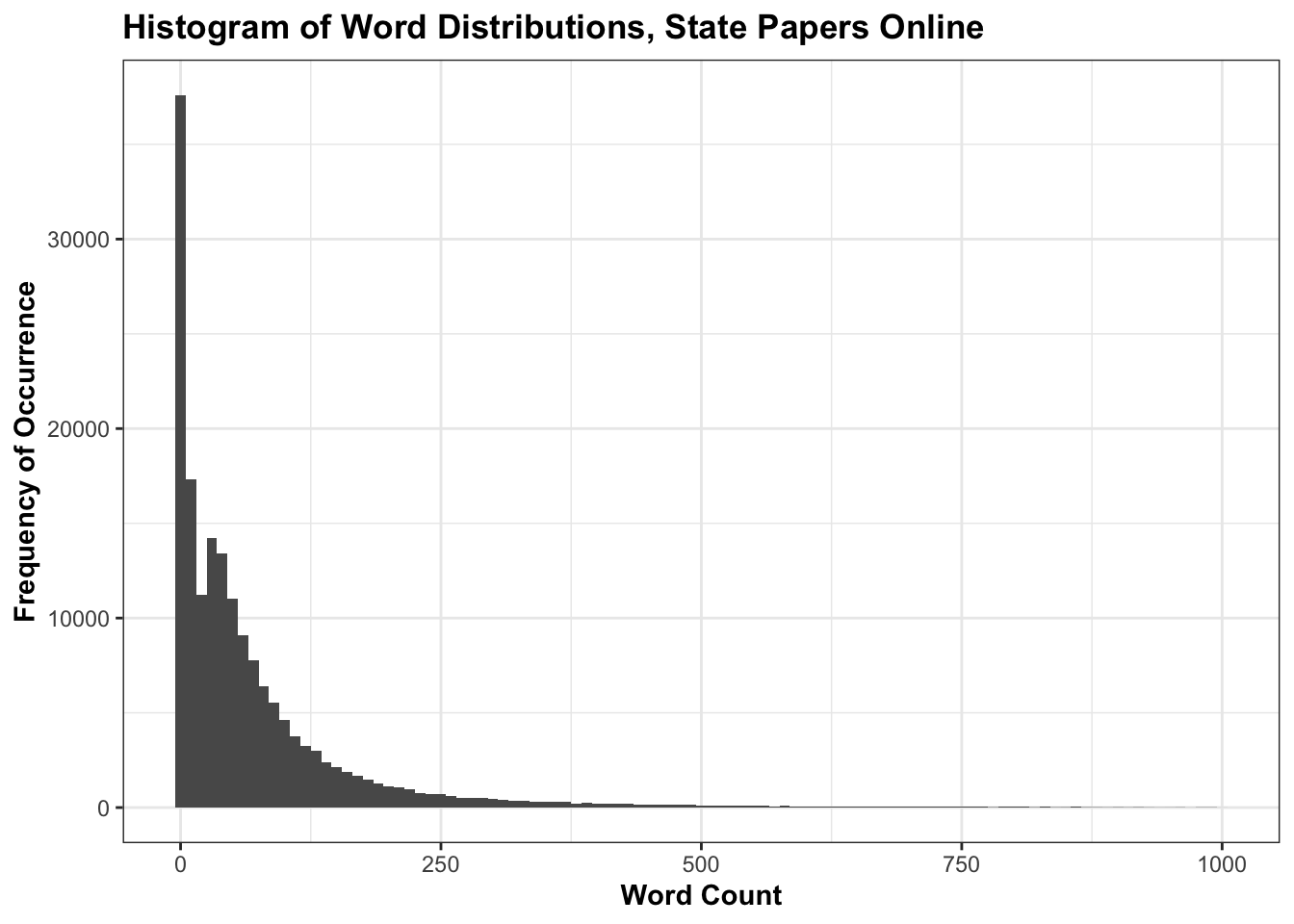

Average Description Lengths

To begin with, it’s worth counting the size and distribution of individual calendar summaries. The whole dataset consists of about 14 million words (a little over 1/3 the size of the most recent printed Encyclopedia Britannica). The entries are generally short: the average number of words per calendar entry is 80. If we look at the distribution of words per document using a histogram, the most frequent entry length is between 0 and 10 words - almost 40,000 documents have a description of this length. It’s a ‘left-shifted’ distribution, which means that most documents are in the smallest category, followed by a smaller number of documents with more words, and so forth. There’s a small number of very long descriptions: the longest is over 60,000 words: that entry is a group of orders sent from Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester to various county sheriffs, which have been bunched together. This very long ‘tail’ has not been visualised.

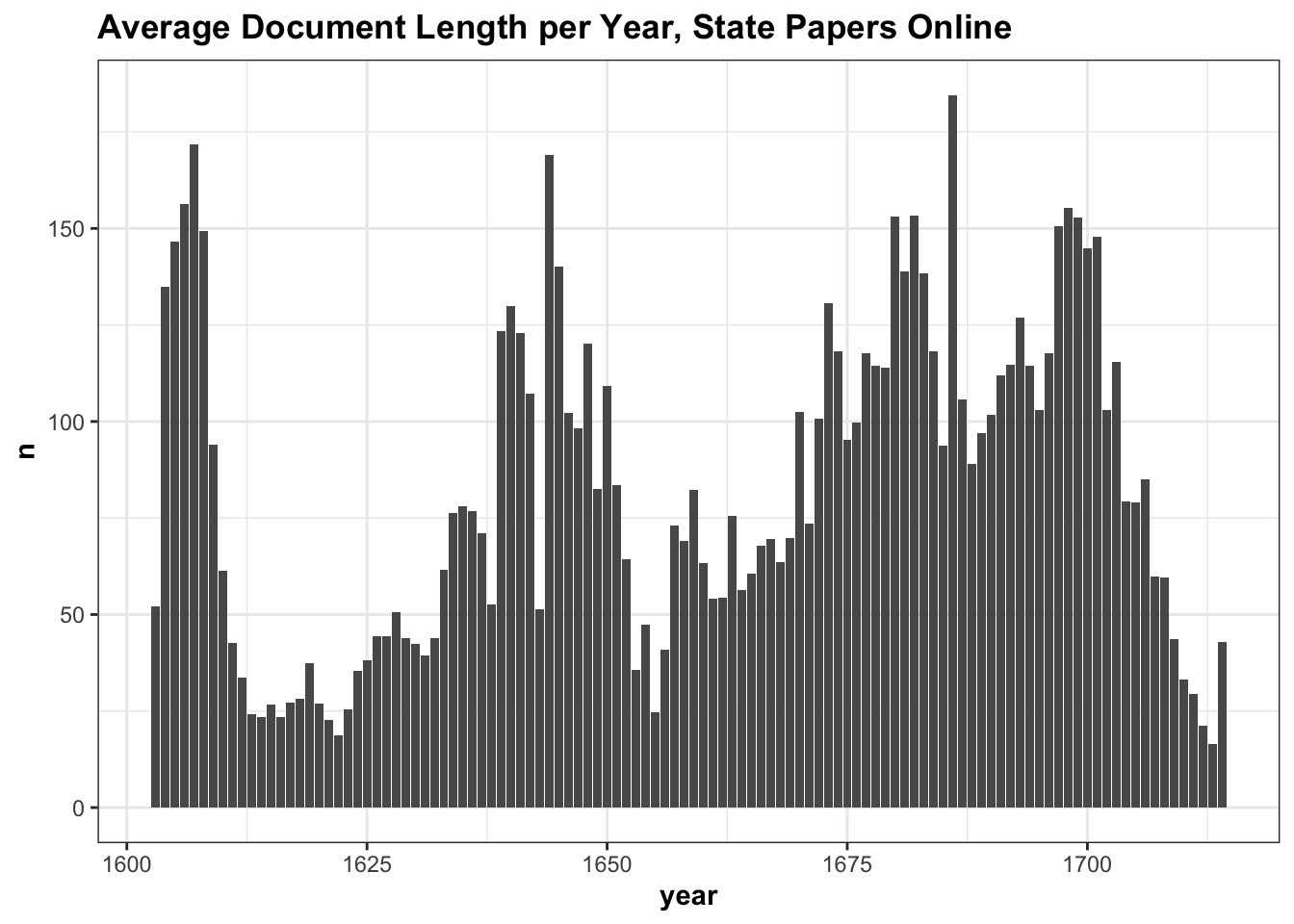

Descriptions over time

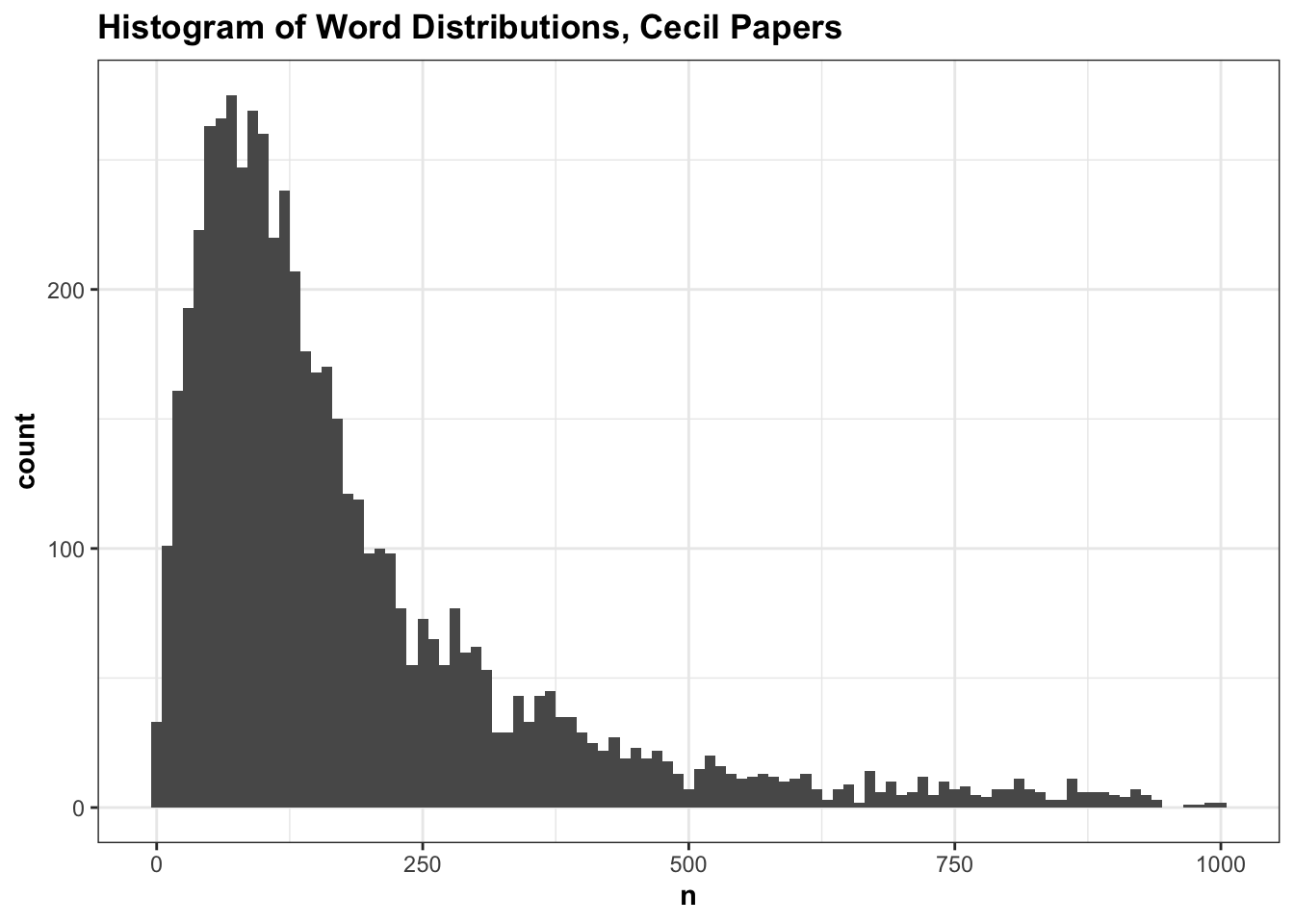

The graph below shows the average description length per year, showing that abstracts fluctuate in length over the century. Much of this can be attributed to different collections. As I wrote above, most correspondence in the State Papers Online from the years 1603-1611 is actually from the Cecil Papers, which were calendared separately (login required) by the Historical Manuscripts Commission, under different editors.

Isolating just the Cecil Papers shows that they have longer descriptions: 236 words, on average. The Cecil Papers also have a differently-shaped distribution: there are few very short descriptions, and in comparison to the rest of the State Papers, the histogram is shifted further to the right: the most frequent number of words is not between 0 and 10, but pretty evenly spread between 50 and 100 words. There’s still a not-pictured long tail (one abstract is almost 6,000 words long).

In the years following the Cecil Papers, the average length of the descriptions drops sharply. This is in part because the foreign series for this period, which make up a lot of the metadata, haven’t really been calendared fully, but are often just lists and indexes with very brief descriptions: mostly all that we have is a date and a description like ‘Buckingham to Coke’. The documents get longer on average during the English civil wars: perhaps because there are far fewer documents in total? The average document length falls again during the interregnum, but slowly increases through the rest of the century.

Calendars and Secretaries of State

The State Papers isn’t just a random collection of all correspondence received by the government, but in fact much of it is documents collected by individual Secretaries of State, while they were in office. We can also look at the document length of correspondence received by each of these secretaries, which can also give clues as to the origins of the calendars.

To do this we took a list of Secretaries of State from Wikipedia, matched to the State Papers data, and filtered to show only documents sent within each Secretary’s period in office. There are two pieces of information visualised here: the bars visualise the average number of words per document, and the total letters sent to that secretary while in office. It’s important because it shows, for example, that it’s not very significant that Henry Sidney has the longest average calendar entry when you realise the State Papers only contains 10 letters written to him.

The chart shows that letters to two of the later secretaries, Daniel Finch and Leoline Jenkins, have particularly lengthy abstracts on average, while Joseph Williamson and Robert Cecil, though at opposite ends of the century, have very similar profiles. One outlier is George Calvert, who received over 1,300 letters while in office, but on average each summary is just under 7 words. While Secretary of State, Calvert concentrated on foreign affairs, in particular the Spanish Match, and these letters have been sorted under foreign entries, and as such have minimal calendar entries.

Text Mining

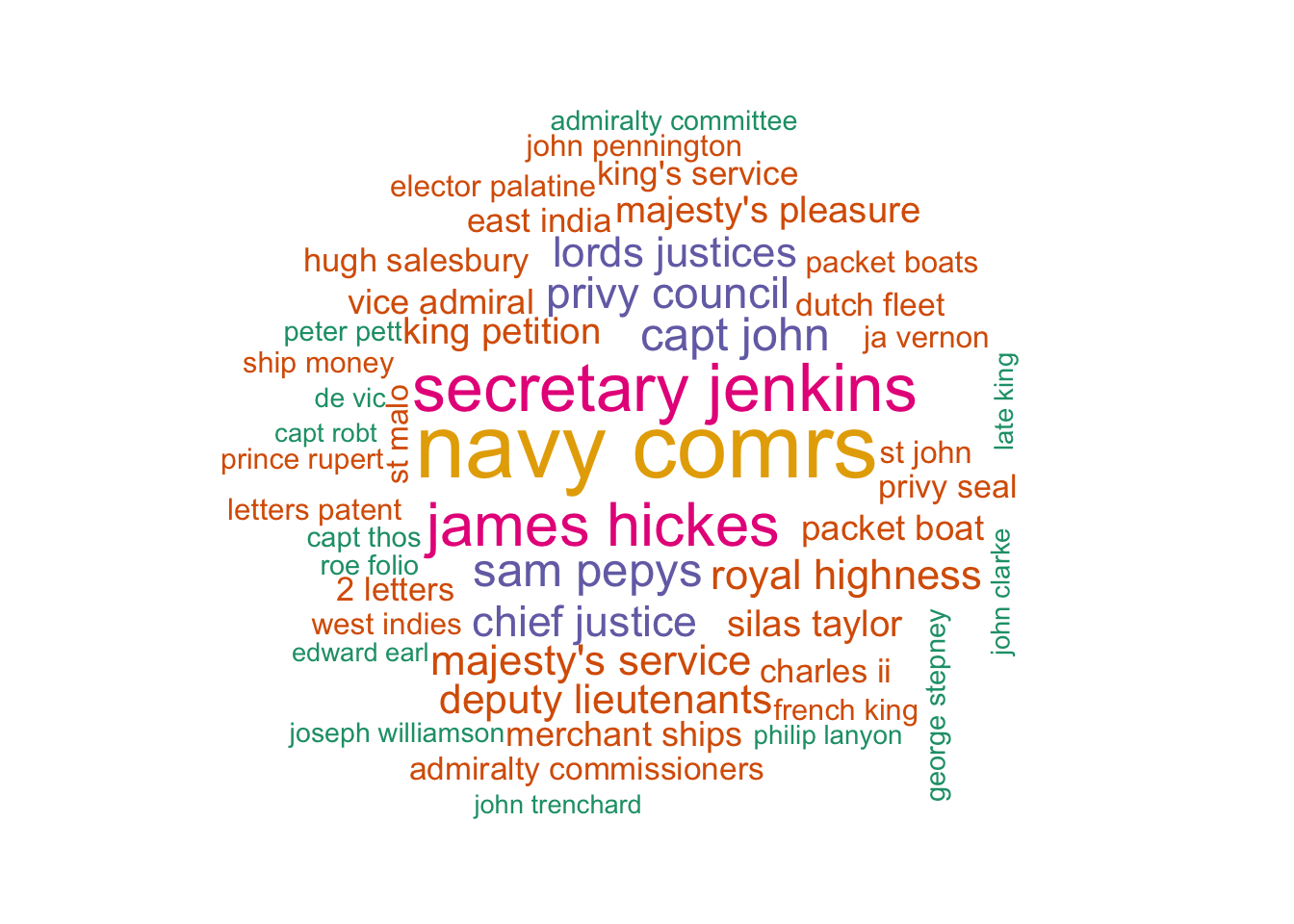

Moving on from counting the number of words, the next step is to analyse the words themselves–a technique which at scale can help to make sense of the content and zoom in on areas of interest. The most basic text mining technique we can apply is simply to count the raw frequency of each word. It’s useful to do some pre-processing here, including removing ‘stop words’ (very common words found in most texts) which tend to drown out more ‘interesting’ terms at the top of any ranked list. A word cloud is a pretty useful way to visualise the top 100 terms: each word is sized by the number of times it occurs.

The wordcloud gives some clues as to the content of the State Papers. We see many names and titles, reflecting the fact that these documents very often relate to specific people, typical correspondence words like send, letter, money, time and so forth, and some words relating to diplomacy such as French, Dutch and war. Other words tell us about the types of letters and instructions contained in the documents: letters, warrant, and petition also score highly. We can also see that much of the correspondence is written to pass information to the state: news, account, and report. There are also words which indicate that other types of letters are asking for something: desires/desire, money, favour.

Another informative analysis is to look at the most common pairs of words - also known as bigrams.

The top pairs of words are generally all very common phrases such as ‘of the’, ‘to be’, and so forth, which I’ve filtered out. The most common pairs of words are very often names, or at least their title and first name (Secretary Jenkins, James Hickes). There are also several more generic titles (Lord Admiral, Royal Highness, Lord Mayor) found here. We also find some navy-related pairs like Dutch Fleet, Merchant ships, East India, and packet boat)

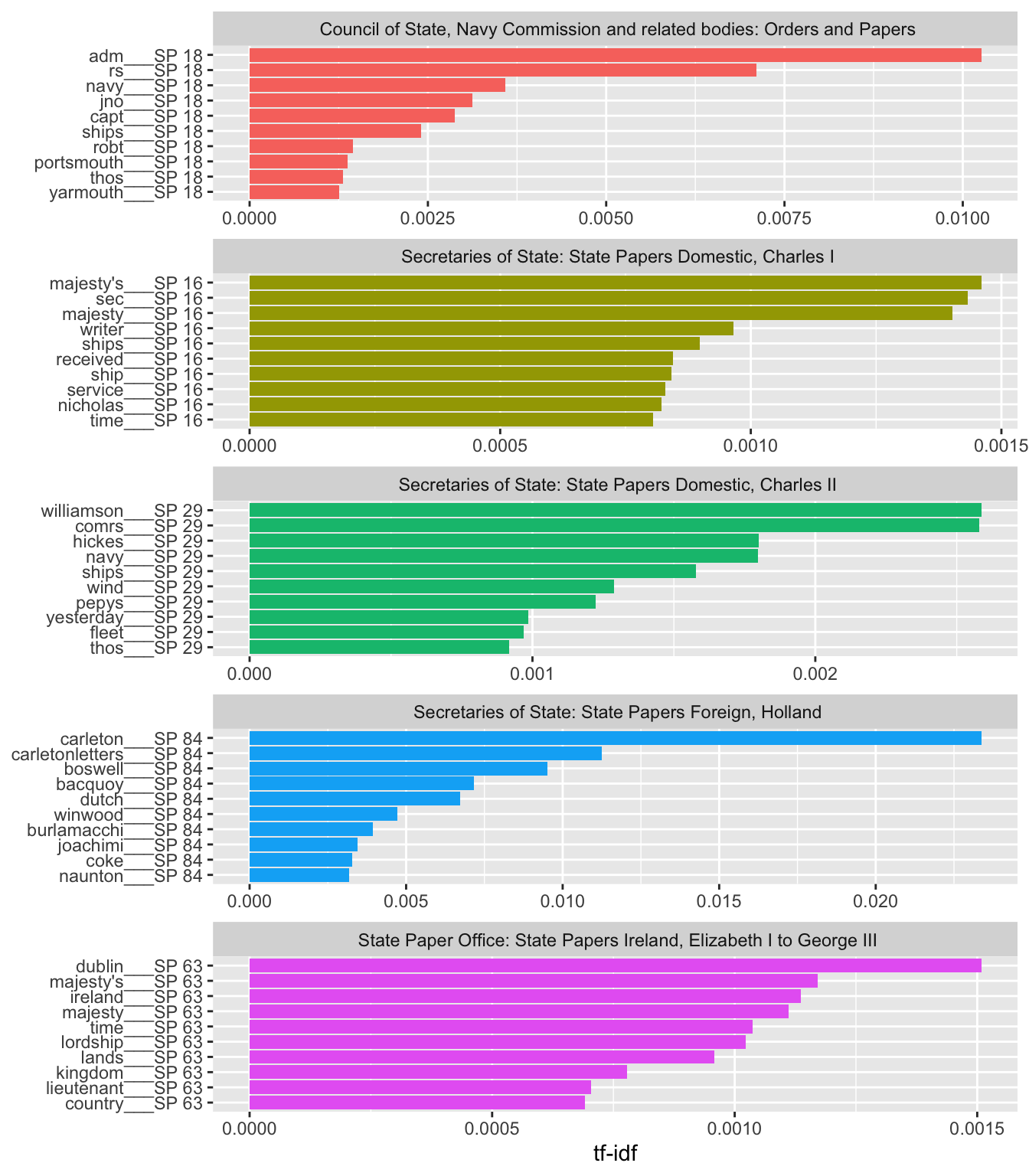

Tf-Idf scores

A very common text mining technique is to calculate what is know as the Tf-Idf score for each word in a document. Tf-idf stands for Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency, and is essentially a measurement of how frequent a word in a given document is, but in proportion to how often it appears in other documents in a corpus. It’s often used in spam filters, for instance to produce a list of words that are likely to indicate a letter is spam but not give too many false positives (although these methods have mostly been replaced by machine learning). Each ‘document’ in the State Papers is a single calendar entry, and they are generally very short. Because of this, it’s unlikely we’ll find interesting results if each entry is considered a single document, because each word will occur just once or twice in each document, at the most.

More informative would be to treat some grouping of entries as a document, and look for the most significant words within that which do not occur in the other equivalent groups. The most obvious one is to treat as a document are the series series: the basic organisational unit of the State Papers. The State Papers is firstly divided into Domestic and Foreign series: the former are then also divided further by reigning Monarch (and the Commonwealth). Looking at differences between the series can tell us how the focus of each reign changed, as well as highlighting differences in the way the archive has been calendared.

We can also calculate tf-idf values for bigrams, to find the most significant.

word | series | n | tf | idf | tf_idf |

browne davies | SP 93 | 63 | 0.36627907 | 10.103935 | 3.7008601 |

consuls browne | SP 93 | 63 | 0.36627907 | 10.103935 | 3.7008601 |

christian iv | SP 75 | 308 | 0.34881087 | 8.158025 | 2.8456079 |

gustavus adolphus | SP 95 | 58 | 0.32222222 | 8.494498 | 2.7371159 |

grand duke | SP 98 | 52 | 0.29378531 | 6.885060 | 2.0227294 |

sigismund iii | SP 88 | 58 | 0.13151927 | 9.410788 | 1.2377001 |

charles ii | SP 98 | 30 | 0.16949153 | 5.869829 | 0.9948863 |

2 copies | SP 92 | 40 | 0.12422360 | 7.464878 | 0.9273141 |

celso folio | SP 85 | 36 | 0.08256881 | 10.103935 | 0.8342699 |

de vic | SP 75 | 107 | 0.12117780 | 6.638200 | 0.8044024 |

Trending Topics: A Google N-Gram Browser for the State Papers

Another typical text mining tool is to look for changes in the frequency of particular word use over time. The Google N-Gram Viewer is a well-known tool which searches some very large corpora of books and displays the change in useage of given words or phrases as a chart. It’s a good way of understanding how the focus of a corpus changed over time, and can be a way of highlighting certain events, or finding patterns in historical concepts. Looking at the word ‘king’, for example, shows that it was used much less frequently during the Interregnum - the period after the execution of Charles I in 1649, when England was briefly a Republic without a monarch. It rises steeply again after the Restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660, peaking in 1663.

Plague highlights three peaks, all relating to outbreaks of the disease in England:

While it can give spurious results (frequency does not necessarily mean a given topic was particularly ‘important’ at that time), this method is a useful way of understanding the narrative of known historical events, or to reveal patterns in particular words. The method can also be used to compare the use of a group of words over time. ‘Treason’ and ‘plot’, tend to rise with each other, for example:

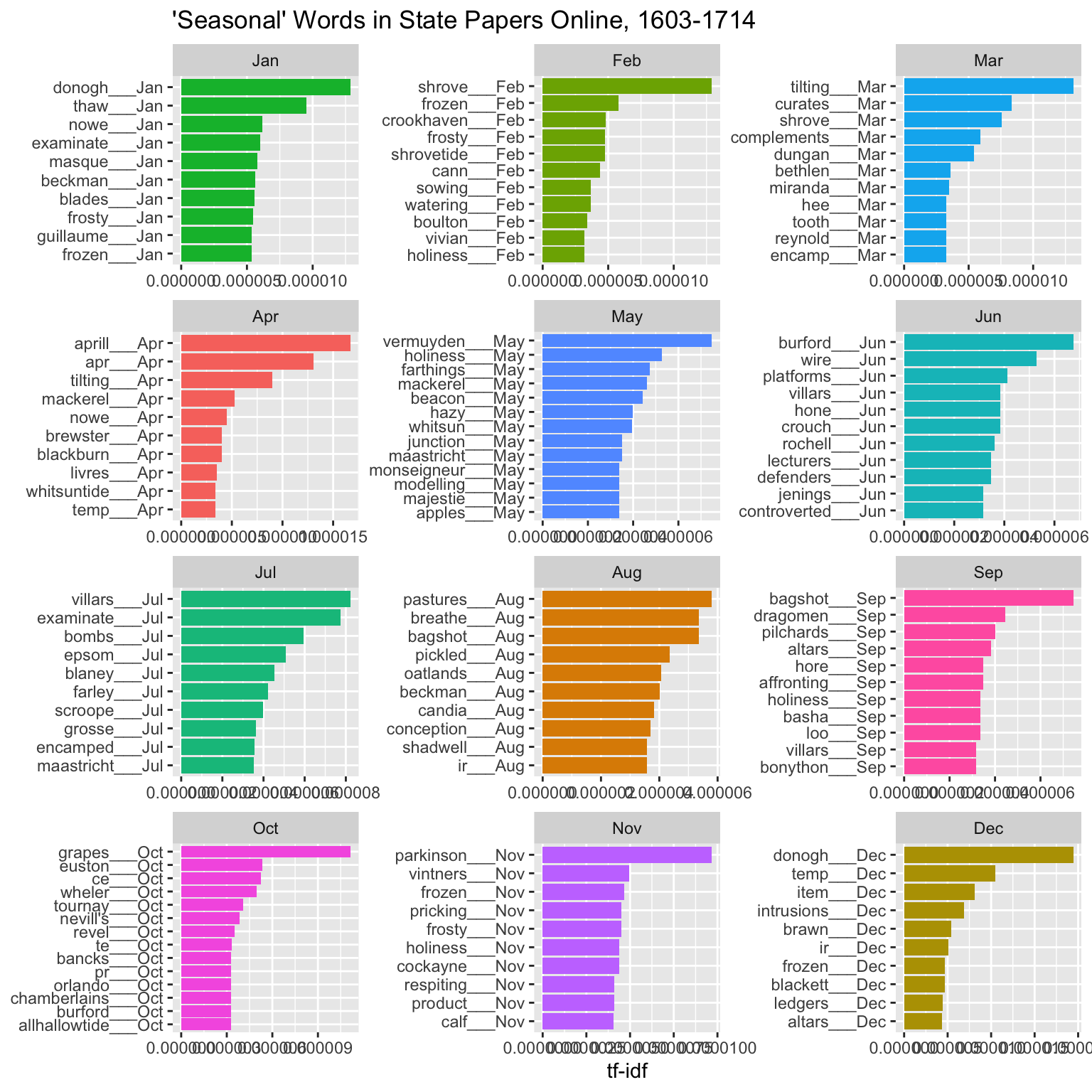

Finding ‘seasonal’ words

Tf-idf scores can help to detect ‘seasonal’ words: words that appear frequently in one part of the year but infrequently in the rest. Noisy data is a problem here. Words which appear very frequently in a single month (say ‘Monmouth’ in June 1683, following the eponymous rebellion) might appear to be seasonal. I wanted to exclude words which appear here because of their appearance in a single month, and also words that occurred very infrequently. To do this I made a rule that included only words which occurred across at least ten years, hoping to filter out unusual words that occurred very frequently in a single month because of some event (there are better ways of finding those).

Some of the results are obviously seasonal words; in other cases it’s more difficult to understand their inclusion. January has masque - a type of play which was often performed at court over the twelve days of Christmas. January, February and November all have unusually high occurrences of the word frozen and frosty, unsurprisingly. February and March have shrove, the Christian festival to mark the beginning of Lent, a moveable feast which takes place in either of these two months; similarly, April has whitsuntide, another Christian festival. The summer months have less obvious patterns: March and April have tilting, a form of jousting, which you might expect to be seasonal though not necessarily so early in the year!

Some other interesting words but not visualised here: Just outside the top ten, August has circuits: a type of court which usually sat in April/May and August/September, so that makes sense. There are a number of harvest-related words like pastures, and grapes, mostly in August and September.

Single events can still, if the frequency is high enough, be enough to push them to the top of the list in this way. I did think it might be possible to find patterns using times series forecasting, which looks for recurring patterns in time series data, but I haven’t had much luck so far…

Conclusions

Text mining covers a whole array of analysis methods, and this post has only scratched the surface. In this case, mining the abstracts proves a good way to understand more both about seventeenth-century events, and the documents themselves. While many of the patterns seen are due more to the practices of collection than actual historical realities, this doesn’t mean that using these methods is fruitless. It’s a useful way to inform searches of the State Papers, for example. The data has shown that it is incomplete and uneven, which means taking care interpreting results. There patterns can be invisible when doing a regular text search of the State Papers. One might search for, say, a keyword relating to the Thirty Years’ War, and end up mostly with documents written long after, in the 1660s, simply because the printed summaries for that period are longer.

However, it’s also clear that some of the patterns within the data are not spurious. Word frequency changes over time often neatly match up with known events (such as plague, war, plot and so forth), and the text even shows seasonal variations - some words appear only at given times of the year, coinciding with seasonal differences in the real world.

I think the key thing is to be aware of the idiosyncracies of the source, when mining a source such as the State Papers. On one hand, the documents are third party summaries (and therefore interpretations), they were written at a particular time for a particular purpose, and are very different in scope and patterns to, say, a corpus of printed books. On the other hand, this ‘timeliness’ of the documents means that they represent a model of information which was updating in real time, and so they can reveal a narrative of events as they were experienced, almost in real-time, as well as instant reactions, at the time they were happening. This makes text mining of a source such as this really exciting and useful.

Further Reading

The best place to start learning these techniques using R is by reading the free online book Text Mining with R: A Tidy Approach

Library Carpentries have a series on text and data mining, mostly using Python through Jupyter Notebooks

The Programming Historian has a very thorough tutorial on calculating tf-idf scores (and why you might use them)